My Comic Book Country

A Launch-Article for Panoptica

My dear friends at Epsilon Theory - Ben Hunt, Rusty Guinn & Matt Zeigler - have finally unveiled Panoptica, their website highlighting the incredible narrative analysis work they’ve been cooking up int he back room for years. The call to action here is to go explore. I recommend starting with their Storyboards:, which let you do things like tease out where we are in a given “trope” like “Social security is gonna go away,” by analyzing years worth of everything written in the English language about the topic:

But, the rest of this is a reprint of a piece I wrote for the launch on America, and my relationship to the idea of it. Enjoy.

Truth, Justice, and the American Way

“Superman was an illegal immigrant.”

You could hear a pin drop.

“Fuck off!” says Subway guy. Subway guy has an “S” shirt on, and is having a rambling conversation with anyone who can’t avoid listening about how bad illegal immigration has made New York. Being fundamentally a coward, I’m usually big on non-engagement, but the irony of this middle-aged, clearly-unwell guy ranting on the subway about immigration while wearing a dirt-standard Target Superman shirt …

… was too much to bear.

I shut up. There’s no ready-for-Reels punchline of hypocrisy. There’s no “aha! I am such a clever liberal elitist! I have owned the unwell!” moment. I cower back into my phone and ignore the rant. Plus, Penn Station is just ahead, so I get off the train and let my heart settle down.

But in the back of my head, I continue the argument. Superman landed in the U.S. from a foreign land and was surreptitiously adopted by locals who forged his birth certificate. He went on to commit countless acts of unsanctioned vigilantism and would absolutely have been the first one ICE targeted in 2025’s Metropolis raids.

Hurr hurr hurr… ain’t I clever?

Silver Age

It’s no exaggeration to say that what I believe about America, my image of what it is and can be and perhaps could and should be, is directly connected to comic books.

I grew up on then-old Silver Age comics. The silver age started in 1956 when the Comic industry self-censored output through their “Comic Code Authority” rules rather than bowing to direct government control.

The Code was mostly concerned about protecting young people from anything related to crime, horror, sex, drugs, or whatever else the group of human individuals who wrote and maintained the censorship code wanted. Wholesalers and distributors would only carry “approved” Comics (a situation which started eroding in the 1970s and died completely by the 2000s).

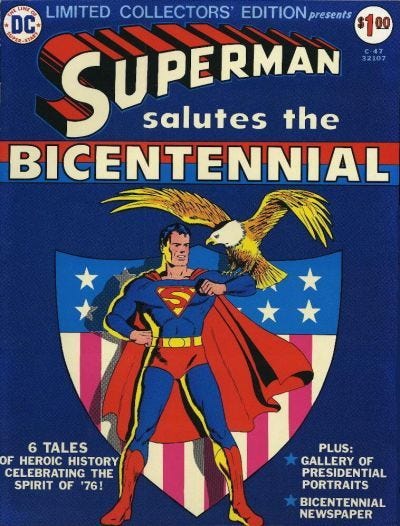

Practically speaking, what it meant was those the yellowed issues stuffed in boxes at the library in Lenox, MA (plus what I could shoplift from the nickle-store in town) were post-war jingoistic American patriotism at its zenith. Superman. The Justice League. Captain America. Sgt. Rock.

When the Bicentennial hit, I was 9, and it was a big deal.

Growing up in the ’70s and ‘80s, the word “Patriotic” didn’t get used in angry conversations at dinner tables so much as it just permeated life. While I was surrounded by counter-culture hippies who’d fled the cities and suburbs to grow weed, play music, make art and write novels, I was constantly reminded that our country was great no matter the actions of its leaders.

As a Boy Scout for much of the ‘70s and early ‘80s, I put on a uniform and marched in every parade alongside veterans. By the time I was old enough to notice, most of those veterans were in their 20s and 30s, not their 50s and 60s. They had not fought the Nazis. They’d had their lives destroyed in Southeast Asia. And yet: they marched along with us and the Shriners and the Rotary Club, carrying flags and rolling in wheelchairs with the scouts.

“The point,” Scoutmaster Kirchner used to tell us, “is that a country is made up of people.” And if we believed in truth, and justice, the melting pot, and the bill of rights, and all the things we had to memorize to get our three citizenship merit badges …

(Community, Country, World),

… then we marched for those beliefs, even if we disagreed with who was in charge.

This performative patriotism – in a rural hippie community – continued for most of my life. Until the pandemic, we had a local tradition of reading the Declaration of independence in full at the local Shakespeare company. We – my local community – believed, fervently, in the idea of America.

Because (as Scoutmaster Kirchner used to say) believing is what makes stuff happen. (He generally applied it more to things like “If you believe you can get up this mountain by sunset, well, you’ve already done the hard part” but the message sank in.)

So we marched.

And I loved it. The flags. The music. The fireworks off the boat dock in the lake. The singing. The reading of the Declaration. But also, even at a young age, I understood the dynamic tension. The Silver Age presented an idealized America. One that the messy, real world could aspire to. I ate it up.

Bronze Age

But I also loved that my conscientious-objecting, quaker, jazz-trumpeter dad would go on drunken rants about Vietnam and the (then ancient) McCarthy hearings and (believe it or not) the rights of “black people and queer folk.”

Part of why I loved comic books is they (unlike most of what I saw on the two channels of TV we could get when the weather was just right) included all of these contradictions. Sure, the true Anti-Nazi silver age stuff was jingoistic as all get out, but the actual comics being printed in the Carter administration were anything but.

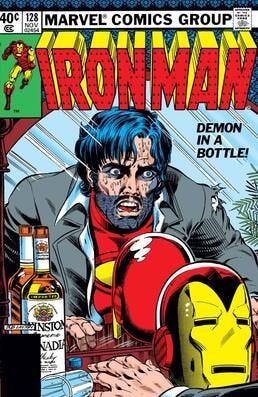

In 1979 I vividly remember reading every issue of Iron Man’s “Demon in a Bottle” run standing in the candy store: I couldn’t bring the story of Tony Stark’s alcoholism home to my alcoholic dad, after all. And I was kind of shocked. So much for the vaunted censorship of the Comics Code Authority.

This was the Bronze Age of Comics – sales might be down, but the social commentary and story telling grew up. While the CCA sticker was still on a lot of books, Comics started asking harder questions. Villains stopped being so obvious. Heroes had warts.

A lot of traditional comics folks hated the 1980s and still do. But Bronze Age Comics explored not just the 4-color gloss of America, but the actual reality the Silver Age and the CCA tried to ignore. Whether it was Iron Man’s drinking or Green Lantern’s drug issues or Howard the Duck, people found a lot to hate. I ate it up.

Modern Age

Almost everything in comics since the ‘80s is usually called “The Modern Age.” In the 1990s, comics nerds were reading the Ur-stories that would become the mass-media version of the “cinematic universes” that are now blockbusters. Sandman. Watchmen. Sin City. Transmetropolitan. Every Marvel plot you’ve ever seen on screen. The Star Wars expanded universe.

For the last 30 years, pick a thorny social or cultural topic, and great writers and artists have been pushing the envelope of what visual storytelling can do. While comics have always had something to say, in the Modern Age the gloves came off. And, like every age before it: I ate it up.

But along the way, “my” comic-book culture became pure, American mainstream culture. I, like most Gen-X nerds, celebrated that we weirdos who got shoved in lockers won the dotcom boom. Games and comics and SciFi and Fantasy are now the foundational, hero-journey stories most kids grow up with in their living rooms. Everyone knows who the X-men are. In the 1970’s, Marvel cancelled the Comic version because nobody cared.

And when something becomes everyone’s, it’s no one’s.

The head of the FBI now hands out “challenge coins” with the logo from the Punisher on them.

A move so wildly incongruous with the actual actions, character, and whole point of the comic book that the creator Gerry Conway once said

To me, it’s disturbing whenever I see authority figures embracing Punisher iconography because the Punisher represents a failure of the Justice system.

So what happens when dumb-as-rocks “mass media” takes over what was edgy “niche culture?”

The niche gets really subversive.

The Post-Modern Age

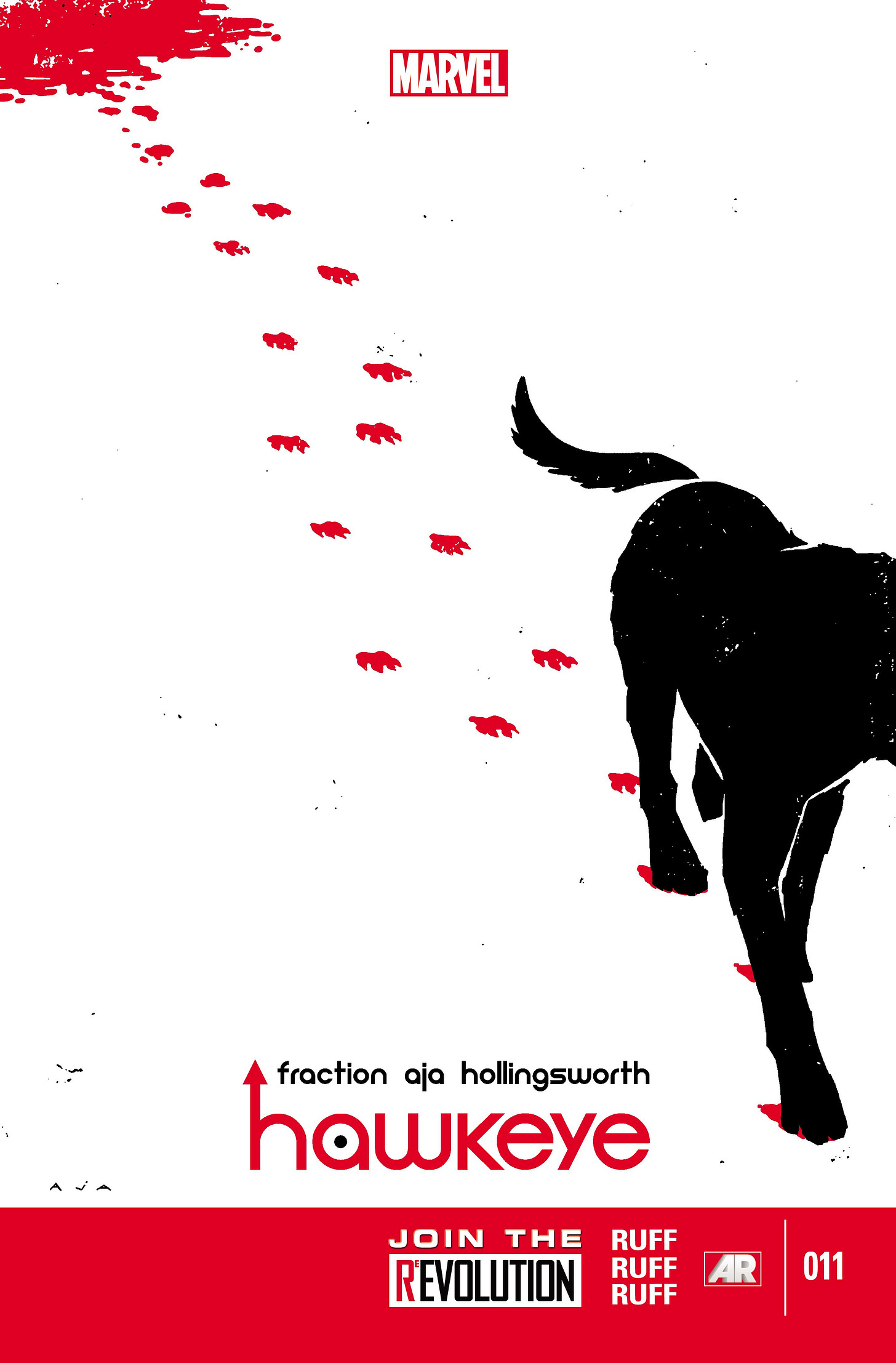

By the authority invested in my by this keyboard, I’ll mark the start of the Post-Modern age of Comics with issue #11 of the Matt Fraction authored run of Marvel’s “Hawkeye.”

Which is told, wordlessly, from the perspective of Hawkeye’s Dog. It’s a brilliant piece of art on the very nature of agency, much less heroism. Arguably the best “superhero” series ever written, it presents our Superhero as a bumbling, self-absorbed, occasionally-competent, largely-forgotten shlub like the rest of us. Which gives the author room to tell a much more interesting story.

This is what American comics are now: a smudged mirror reflecting a less, well, a less comic-book version of a country. And of course: I am eating it up.

The best living comics writer, doing this kind of subversive and important work, is Mark Russell.

Odds are, you have no idea who he is: he’s not in the credits to any blockbuster movies. He’s done workin’-a-job stints at a bunch of Comics titles you might know, like Batman and Superman and Red Sonja.

He’s also the best chronicler of the fall of Silver Age American idealism I’ve read – when a publisher will let him off the leash.

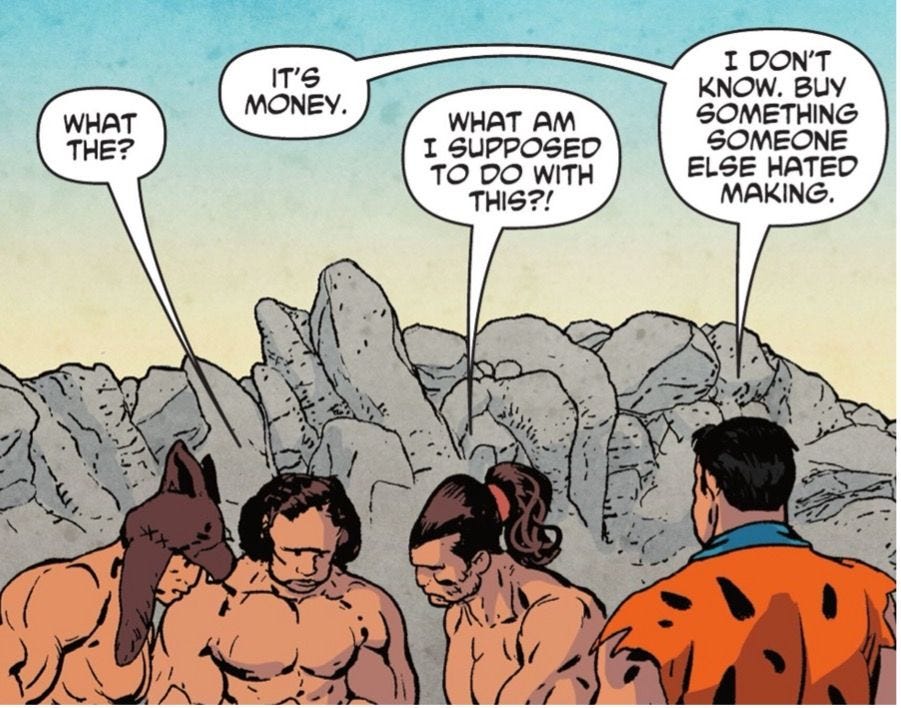

For example, when given a chance to write a Flintstones comic – you know, the Saturday morning cartoon? He turned it into a scathing critique of 21st century American capitalism.

And when given a chance to write Snagglepus – a barely known seemingly-gay lion character from the “Quickdraw McGraw” cartoon, he constructed a brilliant, scathing indictment of culture-war politics through the eyes of the McCarthy hearings.

Obviously, I think you should go read these comics, but that’s not the reason I’m mentioning him and his work. Yes, I think comics are an amazing cultural mirror and more people should read them, but that’s not the reason either.

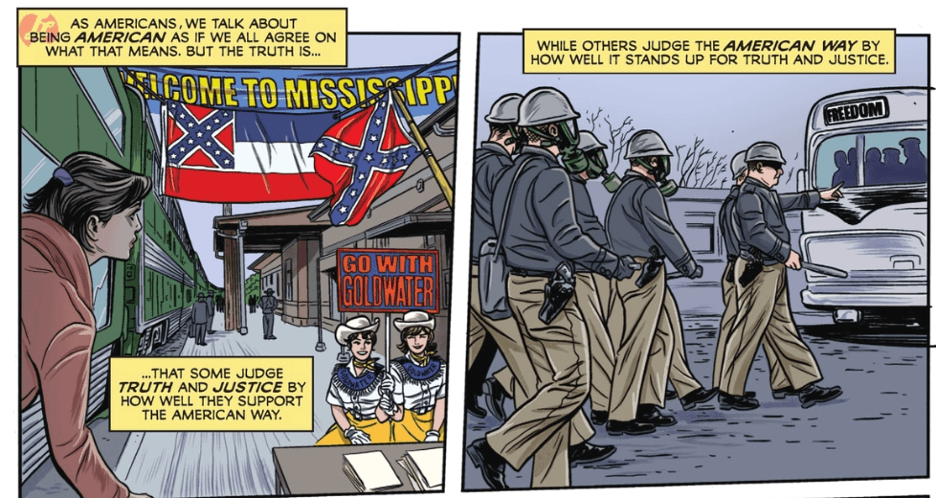

The reason is because of these two panels from Mark Russell’s short lived “Superman: Space Age,” set in 1960s America, where George Wallace was fighting tooth-and-nail to prevent the end of racial segregation.

This is my America.

I choose to believe in all of the Comic Book versions of what America can be. I choose to believe in the fairy-tale version from the 1950s, and the ugly reality of Iron Man’s addictions, and the “just figuring it out” banality of Fraction’s Hawkeye and Snagglepus’ unwavering determination that simply writing truth can make a difference. I think we’re stronger, as a country, when we keep our hearts open to reality, and our eyes lifted towards something better.

I choose to believe that the American Way is to stand up for Truth and Justice. And while I may not be seeing a lot of either right now, I will still march in the parade for that chosen belief.

Truth and Justice are my American way.

Thanks Dave, for writing about our American way so clearly ...I think there are many, many of us who feel the same but couldn't express it nearly so well!